by Victoria Lowe, University of Manchester

Until fairly recently the early sound period in Britain has suffered from critical neglect, due to many of these films’ poor reputations as quota quickies or their uncertain treatment of the spoken word. This has recently been remedied by the work of Porter (2017 and 2020) amongst others but so far there has been little micro analysis of how performance codes were affected by this revolutionary reconfiguration of the sonic, the verbal and the visual. This paper will focus on one of the earliest British sound films, Hitchcock’s adaptation of Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock (1930), starring Sara Allgood as Juno and John Laurie (in his first film role) as her son Johnny. For the purposes of this post, I will concentrate just on two contrasting scenes in the film, one where Hitchcock juxtaposes a lengthily held close up of Johnny’s face (Image 1), with the sounds of singing and a funeral procession, and the final scene of the film, showing Juno lamenting her situation in her empty tenement room. Through this, I will argue that the film (a neglected one, perhaps due to Hitchcock’s stated antipathy towards it[i]), occupies an interesting liminal point, marking the boundary not just between ‘silent’ and sound film, but also between theatre and film (not to mention Ireland and England as discussed by Barr 2011). For the actor, it offered the possibility of a new interplay between the camera, the microphone and the expanded range of tools at the actor’s disposal in terms of voice, expression and gesture. As Charles Barr has argued, ‘the film brings us so much closer than any other surviving records could do to O’Casey’s play as performed by the actors of the time’ (2011: 63). On the one hand then, the film could be understood as seeking to preserve key, iconic stage performances. This is particularly true of Allgood who had also played the part originally at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre in 1924 and in the West End transfer in 1925. (Image 2)

More controversially, the original Captain Boyle, Barry Fitzgerald, was not selected by Hitchcock and a newcomer, Edward Chapman, was bought in to play the part. Fitzgerald ended up with a small cameo as the Orator, in a scene specially written by Casey for the film. His omission has been put forward (Morgan 1994; Barr 2011) as one of the reasons for O’Casey’s rejection of the finished film and its poor reception in Ireland. However, the film also provided an opportunity for a young actor called John Laurie to play the part of Johnny for the first time. Rather than recording an extant performance, Laurie could potentially be treated differently by Hitchcock to allow for the part to be rendered on his own terms. Laurie had a lanky frame and distinctive physiognomy, with large expressive eyes and a bony long face (put to good use of course in a later Hitchcock film, The 39 Steps (1935), when he played the suspicious Crofter). He spends most of the film huddled moodily by the hearth in the background and Hitchcock uses the frame to emphasise his entrapment as he barely seems able to contain his long body in the chair. However, this is contrasted by a number of moments when Hitchcock exploits the extraordinary expressive potential of Laurie’s mobile features and sets it against a strategic use of off screen sound. I will argue that this represents a creative advancement on the ‘close up’ as expressive soliloquy as developed in the silent cinema, but demands more skill of the actor as sound is being recorded simultaneously.

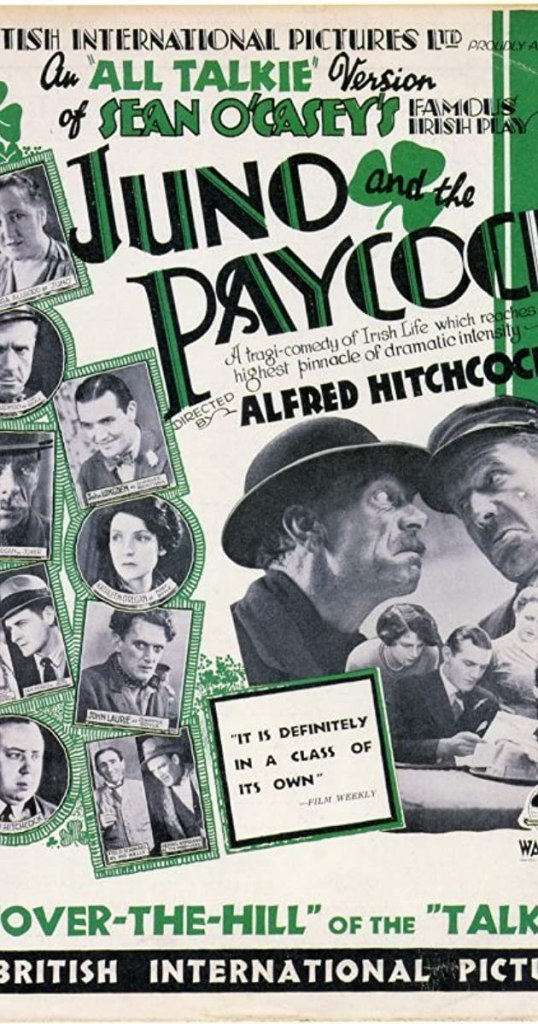

Unlike many other Hitchcock adaptations where the source was downplayed to establish and promote his authorship, Juno and the Paycock was marketed on the basis of the original author rather than the director (Image 3). One passage from the film’s pressbook, though mentioning Hitchcock by name, makes it clear that this screen adaptation was authorized and thus legitimized by O’Casey:

The story told by the film is the same as that of the play from which this talking film was derived, but it differs from the stage play in that Hitchcock has, so to speak, re-expressed it in cinematique-sound terms. This necessitated some further passages of dialogue which were written by Sean O’Casey, the measure of his appreciation of the new form of his work. (BFI Pressbook, Juno and the Paycock 1930)

It is perhaps tempting, particularly in the light of its director’s later dismissals of it, to see the performance codes in the film as being underpinned by a more theatrical style of acting at the ‘expense’ of cinematic naturalism. This is reinforced by debates that circulated at the time around talkie adaptations of plays ‘betraying’ essential cinematic values developed through the non-synchronous sound film (see Porter, 2020: 213) However, such binary oppositions can be misleading. Scholars such as Mayer (1999), Gledhill (2003) and Duckett (2015) have provided more nuanced analyses of the interplay between theatre and film acting approaches prior to 1930. Mayer in particular argues that because contemporary audiences are conditioned to the actor’s performance as validating what the camera sees, what might appear in early film to be anachronistic, ‘stagy’ acting , should be understood more productively as ‘an effective means of explicating narrative, clarifying character relationships, expressing appropriate or valid emotion, or providing aesthetic pleasure’ (1999: 10). More research needs to be done into how much, for instance, the use of gesture and its relationship to the camera frame changed or evolved when voice was introduced into the mix. I have written elsewhere about the early talkie’s negotiation between the visual storytelling of the silent cinema with a move to using the spoken word to express ideas (Lowe 2011). The actor’s part in this was made particularly difficult when, as Porter details, voice recording equipment during filming was initially quite primitive (2017). Cameras had to be encased in padding so that the sound of their operation wouldn’t be picked up by the microphone. Actors also had to deal with the technical challenge of performing to a camera and a microphone. Sometimes, less experienced screen actors, hired for their voices, got caught out trying to shape their performance according to the requirements of the stage.

Turning then to Juno the film, I want to concentrate on two sequences towards the end, one which utilises the expressive potential of the close–up but sets it against an extra diegetic sound-scape; the other develops on the gestural soliloquy of silent film, with an equally expressive use of synchronised voice. Balázs argued in 1924 that film’s ability to hone in on the human face was not only unique to it as a medium, but a fundamental aspect of its storytelling capacity.

‘In close-ups every wrinkle becomes a crucial element of character and every twitch of a muscle testifies to a pathos that signals a great inner event […], when a face spreads over the entire screen in a close-up, this face becomes ‘the whole thing’ that contains the entire drama for minutes on end. (Balázs, 2010: 34)

This then is the principle that underpins Hitchcock’s treatment of Johnny’s penultimate scene. It’s actually a sequence that can rival the celebrated sequence in Blackmail for its use of sound/image relations and actorly performance to give the audience privileged insight into a character’s guilty state of mind. In this scene, the family are celebrating their inheritance with a sing along, but Johnny remains cut off from them, locked into his own fear of retribution for his involvement in the murder of a former comrade. It’s worth noting that the sound and action of this sequence were recorded as performed, i.e the sound of the singing was done with the cast members and full orchestra out of shot. Therefore, Hitchcock keeps his camera tight on Laurie’s face and upper torso for an extraordinarily long time, as he reacts to what goes on around him. Laurie’s expressions play a kind of silent soliloquy as he moves from irritation at the celebratory singing to a widening of the eyes and a sharp intake of breath as the sounds of the funeral start to emerge from the cacophony of noise. As the clip below illustrates he then uses a relaxing and tensing of the breath along with a widening and narrowing of his eyes to indicate the different emotions felt as the scene progresses.

At the end of the scene, Laurie’s lanky body strains upward towards his neighbour, his one arm rigid by his side. As the Mobiliser turns to walk out of the shot, Laurie sinks back down again, looking straight ahead, eyes unblinking and Hitchcock finishes the sequence with a quick cut back and forth to an open window against the staccato sound of gunfire. It’s an unnerving end that works in tandem with Laurie’s wild eyes and jitteriness, ending the sequence, as in the act before this, as effectively as a theatrical curtain. Laurie’s first screen performance here is extraordinary and made even more admirable by the knowledge that unlike in silent cinema where an actor might rely on off screen instructions from the director to guide their on screen reactions, Laurie has sole responsibility for responding expressively (apart from the two cutaways to the Virgin and the Mobiliser) in real time to the sound of the events that are taking place around him.

The second scene I want to look at is also a soliloquy but constructed in a different way to the former. It shows vestiges of the ‘gestural soliloquy’ described by Swender (2006), amongst others, as characteristic of performance in the silent era, and frames Allgood’s upper torso and whole body whilst focussing attention on her expressive use of her hands, white in a palette of greys and blacks. Twisting and turning, or outstretched, they track her movements throughout this final scene from lament to expansive despair. This is underpinned by Allgood’s use of her voice, which reaches a crescendo on the last plaintive appeal to the God who has abandoned her and uses the rhythm of O’Casey’s dialogue, with its repeated phrases (‘my darlin’ Son’) and the repetition of the final phrases (‘take away’ and ‘give us’) to give shape and dynamism to the character’s grief.

These very expressive gestures, through the body and the voice, give a distinctly dramatic end to the film, one that is constructed solely around Allgood’s performance (unlike the end of the play which see Captain Boyle and Joxer return drunkenly from the pub, unaware of the tragedy that has befallen the family). The ringing vibration of her anguished tones in the empty space as she articulates her loss are underlined by the echoing sound, which was rendered in production rather than post production, the delivery of the lines reverberating around a domestically eviscerated, empty space emphasizing Juno’s fate, in particular, and women more generally, as the victims of patriarchal society.

[i] Hitchcock told Truffaut he had not found an effective way to turn it from play to good cinema, stating it ‘has a cumbersome and stagy feel to it as result of the extreme newness and rawness of the apparatus for recording synchronised dialogue which imposed severe restraints on cinematic style’.

References

Balázs, B. (2010). Early Film Theory: Visible Man and The Spirit of Film (originally published 1924). London: Berghan.

Barr, C. (2011). ‘”The knock of disapproval”: Juno and the Paycock and its Irish reception’. In: S. Gottlieb and R. Allen, eds., Hitchcock Annual. Columbia University Press: New York, pp. 63-94.

Duckett, V. (2015). Seeing Sarah Bernhardt : Performance and Silent Film. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Gledhill, C. (2003). Reframing British Cinema, 1918-1928 : Between Restraint and Passion . London: British Film Institute.

Lowe, V. (2011). ‘”Escape” from the Stage?: From play to screenplay in British Cinema’s early sound period’. Journal of Screenwriting, 2(2), pp. 215-228.

Mayer, D. (1999). ‘Acting in Silent Film: Which legacy of the theatre’. In: A. Lovell and P. Kramer, eds., Screen Acting. London: New York, Routledge, pp 10-30.

Morgan, J. (1994). ‘Alfred Hitchcock’s Juno and the Paycock’. Irish University Review, 24(2), pp. 212-216.

Porter, L. (2017). ‘The Talkies come to Britain: British silent cinema and the transition to sound’ in I.Q. Hunter, L. Porter, and J. Smith, eds., The Routledge Companion to British Cinema History. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 87-98

Porter, L. (2020). ‘Okay for Sound? The Reception of the Talkies in Britain 1928-1932′. Journal of British Cinema and Television, 17(2), pp. 212-232.

Swender, R. (2006). ‘The Problem of the Divo: New Models for Analyzing Silent-Film Performance’. Journal of Film and Video, 58(1/2), pp. 7-20.

about the author

Victoria Lowe is a Lecturer in Drama and Screen Studies at the University of Manchester. Her research interests lie in the relationships between theatre and cinema, looking particularly at adaptation, theatricality and intermediality in the cinema. She is also interested in the history of screen acting in the UK. She has published articles examining the relationship between performance and stardom in British Cinema in the 1930s and work challenging the notion of film as a predominantly visual medium by looking at the role of the actor’s voice, both as a signifying and performance practice. Her current research is looking at adaptations between stage and screen, with British cinema as a case study.